28May1924 – 25Oct1944

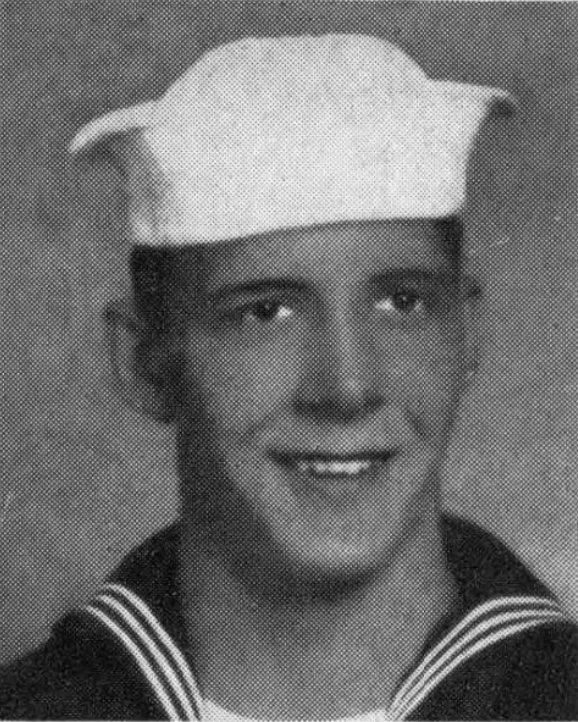

Edison Days

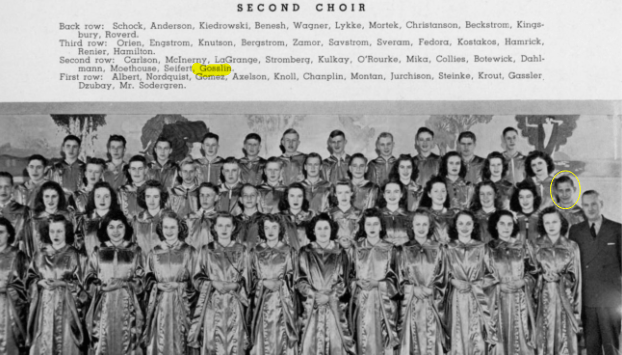

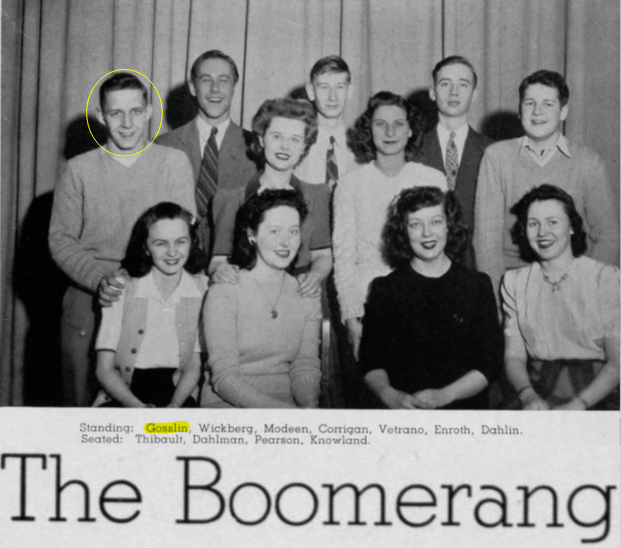

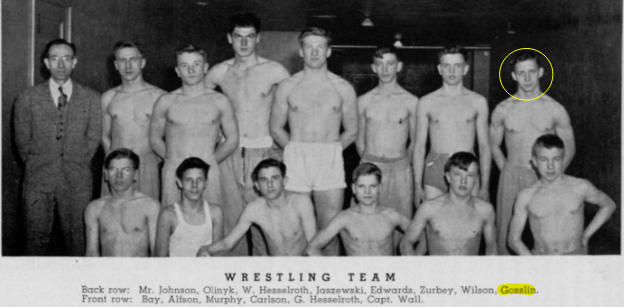

Duane graduated with the Class of January 1944. He was involved with choir, the Senior play, football, and wrestling. He was a letter winner in wrestling.

Military Service

Rate: Seaman 1st Class

Branch: United States Navy Reserve

Shio: USS Johnston (DD-557)

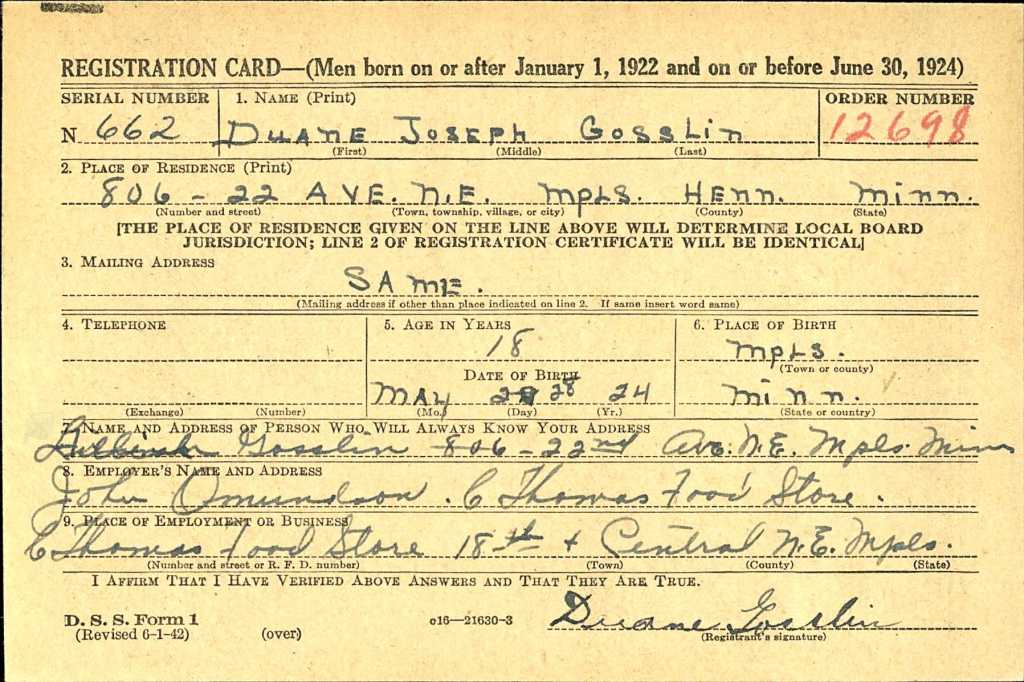

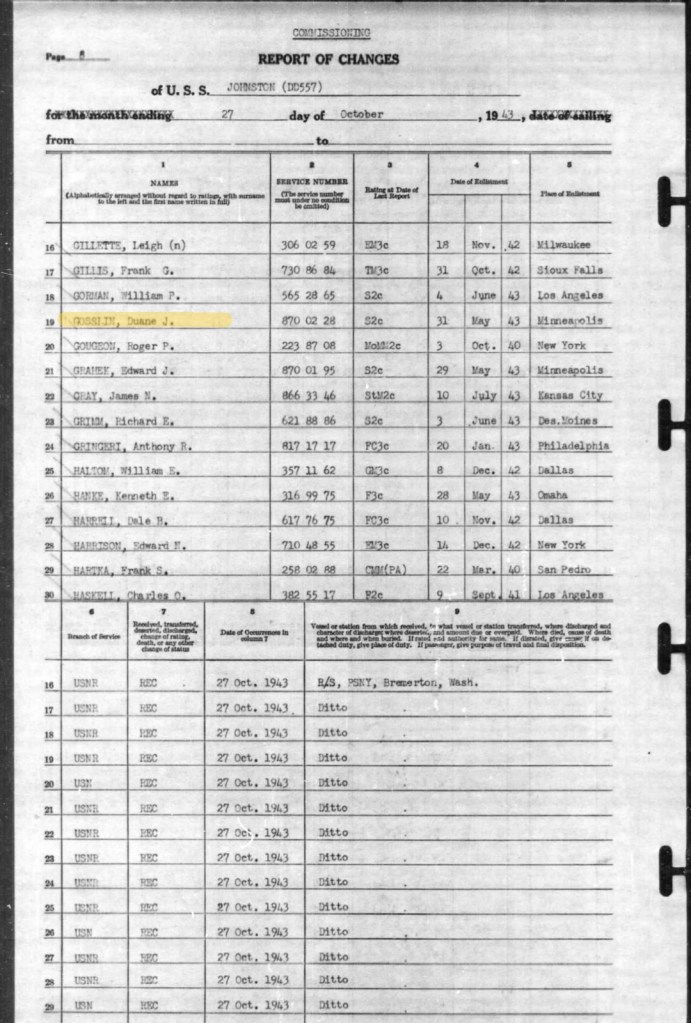

Duane enlisted in the Navy on 31May1943. After basic training, he joined the inaugural crew of the destroyer USS Johnston when it was commissioned on 27Oct1943.

Note: Edison had a program that allowed service members complete their education while serving in the military. It is likely that Duane participated in that program as he is pictured in the 1944 yearbook wearing his Navy uniform.

After a couple of months of sea trials and training, Duane and the crew of the Johnston sailed for the South Pacific.

Entering combat in January 1941, Johnston provided naval gunfire support for American ground forces during the Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaigns in January and February. After three months of patrol and escort duty in the Solomon Islands, she again provided gunfire support during the recapture of Guam in July. Thereafter, Johnston was tasked with escorting escort carriers during the Mariana and Palau Islands campaign and the liberation of the Philippines.

On 25Oct1944, Johnston, supporting the Allied invasion of the Philippines, participated in the Battle Off Samar. The largest naval battle in history, Johnston’s actions that day, are considered one of great “last stands” in US Navy history.

The following long excerpt is from the Naval History and Heritage Command.

The day began with Johnston steaming in the antisubmarine screen for the carriers, sector “F” of formation 5R, and on the morning of 25 October 1944 she had secured from the morning alert when the CVEs had launched their scheduled strikes, their antisubmarine patrols and their local combat air patrols. At about 0650, however, Johnston’s officers and men received alarming tidings – they were “being pursued by a large portion of the Japanese fleet.” General quarters soon rang out on board the ships of the task unit, calling all hands to battle stations. The carriers proceeded in an easterly direction to launch planes, ordnance loads varying considerably within each composite squadron. At that moment, observers in Johnston later recalled, the Japanese bore approximately 345°, about 34,000 yards distant, and closing the range rapidly, with bones-in-teeth at 22 to 25 knots.

Cmdr. Evans immediately called down to the engineering spaces, to light off all boilers and make maximum speed. Without having received orders to do so, he also ordered the engine room to begin making funnel smoke, and the smoke screen generator detail to begin making chemical FS smoke; the detail would expend seven before their work was through. Johnston began to zig-zag, back and forth between friend and foe, smoke billowing from her stacks (black) and her generators aft (white). By about 0700, the carriers had launched their planes to set upon the attacking Japanese force, and began steaming to the southeast.

Estimating the range to the nearest Japanese cruiser as 18,000 yards, Johnston opened fire at 0710 with her 5-inch/38 battery, immediately provoking a response from more than one quarter, with the Japanese heavy cruiser Suzuya firing five salvos of which two appeared to land close aboard. Battleship Yamato fired eleven salvos from her secondary (6.1-inch) battery (0710-0715), and a main battery salvo thundered from the battleship Nagato. Battleship Haruna had already fired five main battery salvoes at TU 77.4.3’s escort carriers; seeing a U.S. destroyer closing rapidly, she shifted fire to her.

The heavy volume of fire headed in Johnston’s direction, in some cases straddling her, prompted Cmdr. Evans to give the order to “stand-by for torpedo attack to starboard,” and the ship turned to head toward the enemy. “This decision was made by the Captain,” Lt. Robert C. Hagen, D-V(G), USNR, the gunnery officer, later explained, “to insure being within torpedo range and to insure being able to fire our torpedoes even though this heavy fire should put the ship out of action before the range had closed. The ship closed to within ten thousand yards of the enemy before torpedoes were fired.”

Johnston bore toward the enemy, her five-inch battery firing rapid salvos, choosing the leading Japanese cruiser as her point of aim, with a target angle of 040°, the speed of target 25 knots. The crew of torpedo tube mount one trained it to 110° relative, the men on mount two trained it to 125° relative. All torpedoes, those in mount one with a 35° right gyro angle, those in mount two with a 25° right gyro angle, were set to run on low speed, at a depth of six feet, with a one degree spread. Using a 2½° off-set, all torpedoes were fired, leaving the tubes at three-second intervals. As best as could be seen, all ran “hot, straight, and normal.”

Johnston maintained the “excellent solution” in her shooting, Lt. Hagen later claiming that his ship’s gunnery had scored at least 45 5-inch/38 AA common hits. After she had launched her torpedoes, Johnston turned into her own smoke screen, and did not actually see her “fish” hit the target, although “two officers and many enlisted men in the repair parties at the time” below the main deck heard “two and possibly three heavy underwater explosions” when the torpedoes were slated to hit. Coming out of the smoke, observers in Johnston saw the leading enemy heavy cruiser “burning furiously astern.” Japanese records would later disclose that one of Johnston’s torpedoes had hit the bow of the Japanese heavy cruiser Kumano, damaging forward watertight compartments and reducing her speed to 12 knots, compelling Vice Adm. Shiraishi Kazutaka to transfer his flag to the heavy cruiser Suzuya. Kumano, thus knocked out of the battle, later retired toward San Bernardino Strait.

Johnston’s emerging from the smoke thus brought her out into the open, and spotters on board Yamato detected the movement and the flagship fired a salvo from her 6.1-inch secondary battery. Moments later, Yamato’s main battery of 18.1-inch guns fired a salvo. The combined effect of those shells hitting the target appeared from a distance to observers on board Yamato and light cruiser Noshiro that the target (Johnston) simply disappeared.

Johnston, however, was very much alive, although badly battered. The elation that Johnston’s sailors felt over the damage they believed they had inflicted on the enemy soon gave way to shock and horror as three 18.1-inch shells from Yamato tore into the ship in addition to three 6.1-inch from the same battleship. At about 0730, three of the former (18.1-inch) hit aft, knocking out the after fire room and engine room, all power to 5-inch mounts 53, 54, and 55, all power to the steering engine, rendered the gyro compass useless, and cut her speed to 17 knots. Escaping steam from the no.2 engine room killed or badly burned every man in the handling room for Mt. 53 and forced the temporary abandonment of that compartment. Steering had to be done manually, at steering aft (which was not equipped with a gyro compass) orders having to be passed from the bridge by the JV phones. The 6-inch hits disabled the 40-millimeter director on the after stack, and the combined force of the shells hitting the ship snapped off the SG radar. Two 6.1-inch shells hit the bridge on the port side, one passing aft of the port side torpedo director and the other exploding, killing Lt. (j.g.) Joseph B. Pliska, D-V(G), USNR, DesDiv 94’s recognition officer (specially trained to differentiate friend from foe) on board on temporary duty, outright, as he stood next to Cmdr. Evans, who emerged sans helmet, bare-chested and bleeding. When Lt. (j.g.) Robert Browne, MC-V(G), Johnston’s medical officer, reached the bridge, Evans sent him to treat those more seriously wounded, then wrapped a handkerchief around bloody stumps of his fingers, much in the manner in which Cmdr. J. R. M. Mullany calmly applied a tourniquet around his nearly severed arm at the Battle of Mobile Bay during the Civil War. There was a battle to be fought.

Providentially, Johnston encountered a rain squall, and received ten minutes’ grace to evaluate the catastrophic damage she had just received. The FD radar, rendered inoperative, was soon back in operation, just in time to take a Japanese destroyer under fire at a range of 10,000 yards “under modified radar control.” With the radar detecting Japanese ships closing the formation rapidly, Johnston engaged a cruiser at 11,000 yards, firing a total of over 100 rounds at the targets not seen but only indicated on radar.

At about 0800, Rear Adm. Sprague ordered the “small boys,” escort vessels and destroyers, to attack with torpedoes. Although Johnston had already fired all ten of her 21-inch torpedoes, she slid in astern in the boiling wakes of the destroyers Hoel and Heermann and destroyer escort Samuel B. Roberts (DE-413) to provide fire support. “Firing was continued intermittently on the then closest enemy cruiser,” Lt. Hagen wrote later, and he noted experiencing difficulty of gunnery control “staying on the target due to radical movements and loss of own ship’s course.” After the “small boys” had launched their torpedoes, Johnston turned to retire, closing the range on what appeared to be a Japanese cruiser. At 6,000 yards, the destroyer opened fire and obtained “many” hits. Johnston’s fire discipline proved exemplary, she trained her main battery on one of the escort vessels as she emerged from a smoke screen, close aboard. With the DE being identified as friendly, the director was trained off target, but one hot loaded gun had a powder case “cook off” and a “near miss” splashed just ahead of the U.S. ship.

With the destroyers ordered to return to the formation, Heermann received orders from the OTC (Rear Adm. Sprague) to engage Japanese cruisers firing on the carriers from the port quarter. Heermann took station on what she believed to be Hoel, but which turned out to be Johnston. Realizing the case of mistaken identity, Heermann began nevertheless to take station on Johnston, to proceed into battle as one section, but Cmdr. Amos T. Hathaway, her commanding officer, soon realized Johnston’s dire predicament – she was obviously slowed and damaged. Going it alone seemed to be the only viable option at that juncture, so Heerman set course to proceed on her own. At that moment, however, Johnston signaled: ONLY ONE ENGINE X NO GYRO X NO RADARS.

Heermann backed emergency to clear Fanshaw Bay, then crept ahead, increasing speed and passing astern of the flagship. Heermann discerned Johnston on her port bow, then turned right to bring her 5-inch/38 batteries to bear on the enemy ships known to be close aboard, and stopped, her commanding officer expecting the badly damaged destroyer “to pass clear ahead.” From Heermann’s bridge, however, Johnston “appeared to be swinging left very slowly” so the former’s commanding officer ordered her backed “emergency full.” The men on both ships in a position to witness this drama in the midst of battle all “believed that the ships would collide.” In the midst of what history would record as one of the most important naval battles ever fought, two destroyers drew inexorably nearer, the distance between them lessening with each tick of the chronometer. Ernest Evans had Johnston backed full on Johnston’s one good engine, however, and Johnston’s bow missed Heermann’s “by about three inches [author’s italics].” In a demonstration of the American sailor’s recognizing amidst adversity what must have seemed miraculous, “a very loud spontaneous cheer,” wrote Cmdr. Hathaway, “arose from all hands on the topside of both vessels.”

The collision having been avoided (“by the narrowest possible margins,” Lt. Hagen wrote), Johnston worked back up to her top speed (17 knots) on her one engine and re-entered the fray, soon to encounter a Japanese battleship emerging from the smoke, 7,000 yards distant, on the port beam. Cmdr. Evans having “given the order not to fire on any target unless we could see it…enemy and friendly ships…now in the melee.” CIC had reported the contact to gunnery control and Johnston immediately opened fire given her obtaining a visual sighting. Lt. Hagen later claimed “several hits…on the pagoda superstructure” as the destroyer fired approximately 40 rounds “at [her] necessarily reduced rate…”

With Johnston steaming to the southwestward on her one good engine, several miles astern of TU 77.4.3, Cmdr. Ernest Evans kept the picture “in mind …at all times” of Japanese battleships and cruisers on her port quarter. Japanese destroyers steamed on her starboard quarter, at ranges that varied from seven to twelve thousand yards. Johnston made liberal use of smoke to cloak her position.

At about 0830, however, Evans saw Gambier Bay “under heavy fire [from] a Japanese heavy cruiser,” so ordered Johnston to draw fire from the embattled escort carrier. Closing the range to 6,000 yards, the destroyer unsuccessfully attempted to draw fire from Gambier Bay, then checked fire at 0840 to engage enemy destroyers that were clearly closing the other CVEs rapidly. Upon receiving that information from CIC, Cmdr. Evans set course toward the column of destroyers, with what appeared to be a destroyer leader in the van, followed by two three-ship destroyer divisions. Sighting them at 10,000 yards, Johnston opened fire on the leader, Lt. Hagen recounting later that the ship’s gunnery seemed to be effective as the range closed to 7,000 yards, the warsghip scoring a 5-inch hit on the light cruiser Yahagi on her starboard side, forward damaging an officer’s stateroom. While she seemed to be scoring hits, however, she was also receiving them as well.

At about that time, as Hagen later marveled, “a most amazing thing happened,” when the destroyer leader executed a 90-degree turn to starboard, breaking off the action. Cmdr. Evans tried to maneuver Johnston to cross the “T” of the second destroyer in column, but before that could be accomplished, the six remaining Japanese ships turned and began to open the range.

Shortly before she opened fire on the Japanese destroyers, Johnston received a TBS message directing the “small boys” to “interpose [themselves] between the carriers and Japanese cruisers on their port quarter.” As the Japanese destroyers that Johnston had been engaging broke off the action and steamed off, Cmdr. Evans checked fire and had his ship steam toward the enemy cruisers, for the next half-hour engaging first the cruisers on the port hand and destroyers on the starboard, alternating between the two, Lt. Hagen later stated, “in a somewhat desperate attempt to keep all of them from closing the carrier formation.”

About that time, a shell hit Mt. 52 by the pointer’s seat, wrecking the mount and killing the mount’s crew and starting fires in the handling room. Smoke and flame in proximity to the bridge further added to the difficulties of command, as two hose parties attacked the flames. Another shell hit radio central, killing or wounding every man there, another set fire to a 40-millimeter magazine, shells began cooking off and dense smoke resulted from the hit. Cmdr. Evans sent messengers with steering instructions, then, at about 0920, went aft himself to the fantail, traveling the length of his ship that had suffered heavy, almost unimaginable damage, picking his way aft across the torn and blackened decks, then conning her movements from there “with only his seaman’s eye and knowledge of the relative position of enemy ships to guide him.”

Johnston taking hits “with disconcerting frequency” [from 0910 on, Lt. Hagen noted, “we sustained numerous hits up and down the length of the ship”] continued until she found herself about 0930 with “two cruisers dead ahead…several Jap destroyers on our starboard quarter and two cruisers on our port quarter. The battleships were well astern of us.” Sailors at the fantail scuttled the depth charges in the tracks at the stern so that the charges would not explode among men abandoning ship if it came to that. Machinist Marley O. Polk, on board less than a month, learning of serious flooding in the compartment containing the main condensers, volunteered to go below and close the overboard discharge valve. Fully aware of the dangers inherent in that course of action, Polk navigated the flooded space open to the sea and managed to reach his objective. Sadly, Japanese shells continuing to plunge into the ship’s engineering spaces killed him in the act of closing the valve. Polk’s courageous devotion to duty resulted in his receiving the Navy Cross (posthumously).

“At this fateful time,” Hagen wrote later, “numerous Japanese units had us under very effective fire, all of these ships being within six to ten thousand yards of us. Shortly after this, an avalanche of shells knocked out our lone remaining engine room. Director and plot lost power. All Communications were out throughout the ship. All guns were out of operation with the exception of five inch gun number four that was still shooting in local control. As the ship went dead in the water [hits in no.1 fire room at 0940 finally stopped the starboard engine] and its fate long inevitable, the Captain gave the order to abandon ship at about 0945.”

After word came to abandon, Lt. Browne, Johnston’s medical officer, who had just turned 28 years of age on 2 October, remained, providing life jackets to wounded men who did possess them, then directed them off the ship. He was last seen in the wardroom, tending to the wounded. The plunging fire of the Japanese, however, cut short his courageous efforts as the battered destroyer continued to take fire from an enemy who most likely neither knew nor cared that their target had the will, but not the means, of fighting back. Browne’s selfless heroism resulted with his being awarded a Navy Cross (posthumously).

All of the men capable to do so then left the ship by about 0955, Johnston still under constant bombardment of the enemy as her sailors lowered the gig, which soon sank, having been holed by shell fire, and four life rafts into the water. The floater nets proved another matter, their racks probably having been seriously damaged and mangled by shell fire; her men only succeeded in freeing two before the ship rolled over and sank by the bow at 1010, in 5,000 fathoms of water. The ship went down “several miles behind the task force and practically surrounded by the enemy.” One Japanese destroyer approached within 1,000 yards “to make sure that the ship had sunk.”

Of the 327 men on board Johnston at the beginning of the battle (326 officers and men of her ship’s company, and Lt.(j.g.) Pliska from DesDiv 94), she suffered 50 killed in action and 45 who died of wounds or exposure. Originally listed as missing in action, the 91 men who were never recovered and initially listed as missing, were later classified as presumed dead a year and a day after they had been declared missing.

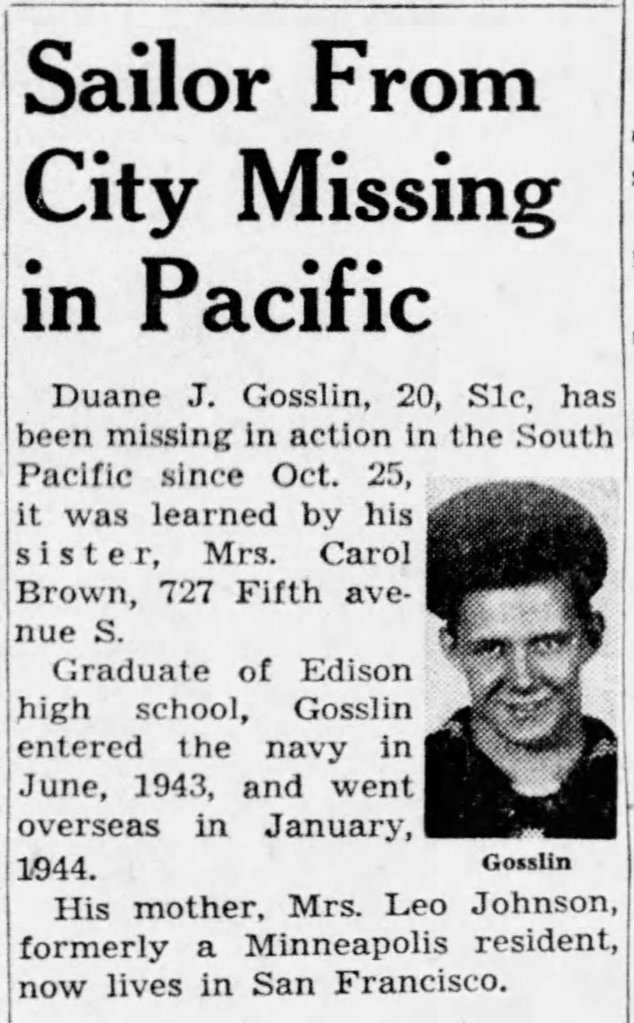

It is unknown if Duane was one of the 50 men killed in action, or if he was able to abandon ship and went missing after. His family was informed that he was missing in February 1945.

Duane’s official status is missing in action. His name is one of 36,278 names on the Tablets of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery in Taguig City, Philippines.

A headstone with Duane’s name, and the name of his sister Joyce, is located at Hillside Cemetery in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

In 2019 an expedition discovered the wreck of the USS Johnston. In March 2021 the wreck was positively identified and filmed. Lying over 20,000 feet below the surface, at the time, it was the deepest wreck ever found.