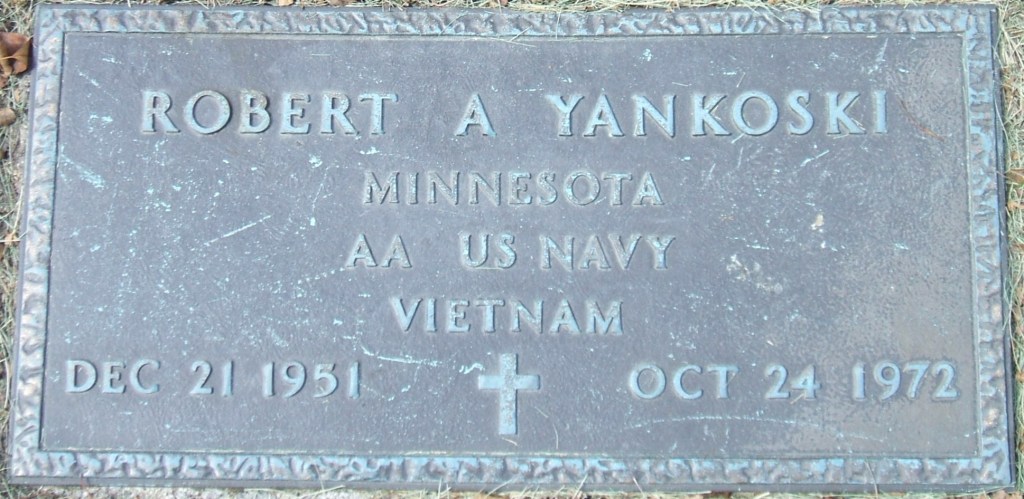

21Dec1951 – 24Oct1972

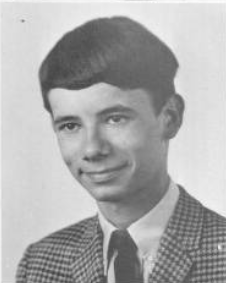

Edison Days

Robert graduated with the Class of 1970.

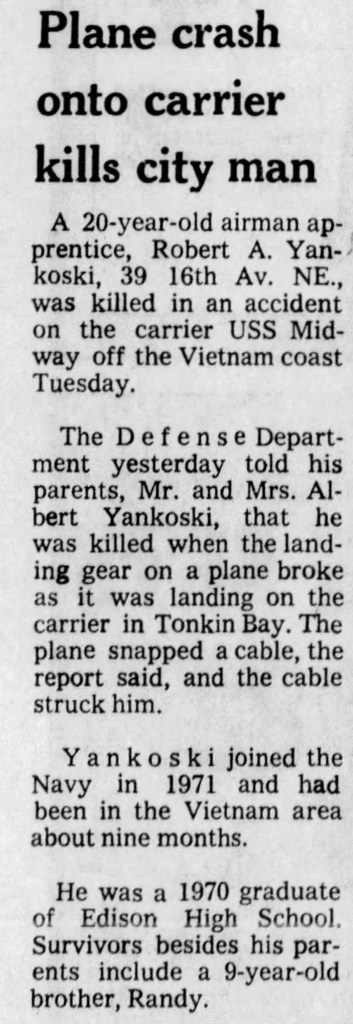

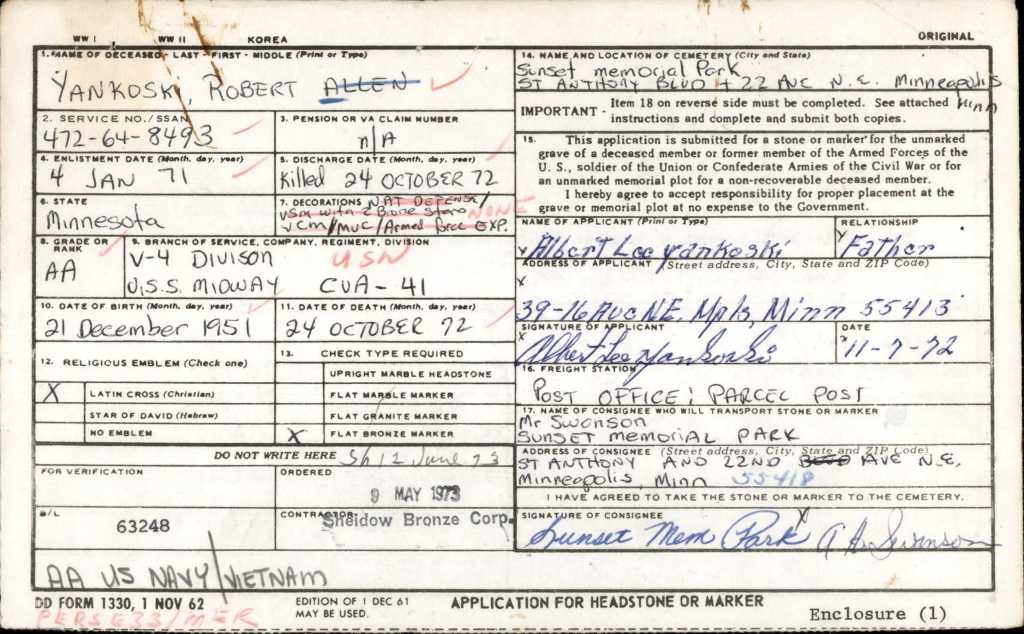

Military Service

Rate: Airman Apprentice

Branch: United States Navy

Ship: USS Midway (CV-41)

Robert enlisted in the Navy on 4Jan1971. At some point after basic training, he found himself aboard the USS Midway aircraft carrier as an Airman Apprentice. As an Airman Apprentice, Robert was doing on the job training on the flight deck of Midway to support the launching and recovering of planes. The flight deck of an aircraft carrier is considered to be one of the most hazardous work in environments in the world.

On 30Mar1972 the North Vietnamese military launch a major attack across the demilitarized (DMZ) in an effort to seize territory and destroy the South Vietnamese army ahead of the Paris Peace Conferences planned for later that year.

The Midway was in port in Alameda, CA when the attack started, having returned the previous November from a 6-month tour in support of the war efforts in Vietnam. On 10Apr1972, seven months ahead of schedule, the Midway left port bound for Vietnam to help defeat the North Vietnamese offensive. On 11May1972, the Midway began combat operations over Vietnam.

The following excerpt is from a first-person narrative written by Bruce Kallsen (USN Ret.) who was the pilot of the plane involved in the incident in which Robert was killed.

Thank you Bruce for allowing this excerpt to be included.

It was the 24th of October, 1972, and I and my Bombardier/Navigator (B/N), “Bix”, were returning to the USS MIDWAY in our A-6 aircraft from a night low-level bombing mission over North Vietnam. Upon contacting the ship, we informed them we had two “hung” 500-pound bombs, ordnance we had tried in vain to drop. It was the ship’s call as to whether we brought the ordnance aboard upon landing or jettisoned it at sea. The disadvantage to jettisoning was that it required jettisoning the Multiple Ejector Rack (MER) as well. The MER was a $5,000 piece of equipment that transformed a single wing station into one capable of carrying up to six bombs, and MERs were in short supply. Complicating the matter: the bombs were hung on station 5, farthest outboard on the wing. Their combined weight and moment arm put the aircraft right at the limit of maximum asymmetric load for an arrested landing. Since naval aviators as a group are quick to volunteer in difficult situations, decisions such as this were left to the ship/airwing/squadron representative and were based upon the circumstances and individual pilot’s prior landing performance. The powers that be directed that we bring the bombs aboard.

The landing was further complicated by additional factors: There was no natural wind, so the aircraft carrier would have to create the wind over the deck through its own speed through the water. Since the landing area was angled 13 degrees to the left of centerline, this meant there would be a crosswind coming from the starboard side. Additionally, it was a dark, moonless night, with no discernible horizon, the bane of the naval aviator. Maintaining wings level on final approach would be a challenge. Also, the aircraft had been approved in the previous year for increased “maximum weight” arrested landings. The new limit was 36,000 pounds, vice the 33,500 pounds previously authorized. Our predicted landing weight was 200 pounds under the new maximum. Finally, the flight deck was “heaving,” slowly rising and falling with the swells of the sea. All night carrier landings are difficult, but this one would be especially tricky.

The approach to the ship was normal, and at 3/4 mile, Bix called the “ball,” indicating we had acquired the “meatball” landing aid and were commencing our visual approach. Nearing the midpoint of the approach, the ball went high, the LSO (Landing Signal Officer) called me high, and I had already made the correction he was calling for to put us back on the optimum glide slope. Another “you’re high” call was made, and I corrected again. At the time I thought the second call was also from the LSO, but it turned out Bix had made it, something he had never previously done. The touchdown brought with it the immediate realization that things were not normal….WE HAD CRASHED!!

Unknown to us at the time, the starboard axle had sheared upon contact with the flight deck, and it was now an uncontrolled missile careening up the flight deck. The stub of the starboard landing gear was dragging on the flight deck, causing a pronounced right-wing-down orientation. My reaction was the normal for all arrested landings; I applied full power in the event the aircraft failed to engage the arresting wire. Unfortunately, the starboard stub caught the arresting wire, the cross-deck cable normally snagged by the tailhook. As the wire minimally slowed our forward progress, the aircraft tilted far over to the left, threatening to roll inverted. Flashes of being upside down under a burning aircraft crossed my mind, but as quickly as the crash had occurred, the wire slid down the length of the landing gear and released its hold on our badly crippled conveyance. The aircraft fell back to a right-wing-down attitude as I continued my efforts to power the aircraft off the angled deck. It was apparent we were going too slowly to have adequate flying speed if we left the flight deck, but I felt we could get the aircraft off the deck and then eject. Unfortunately, the laws of physics demanded otherwise.

As the right landing gear stub continued in a howling screech to drag up the flight deck, it caused the trajectory of the aircraft to slowly arc to the right, out of the landing area, and into the pack of aircraft at the front of the flight deck. Immediately in our path was the F-4 just landed by our Air Wing Commander (CAG), with CAG climbing out of the cockpit. Undeterred I continued at full throttle, with the aim of shoving the F-4 off the flight deck, following it, and ejecting. Again physics intervened, and the result was the dismembering of the left wing and tail of my aircraft, and a forward displacement of the F-4, breaking CAG’s leg rather severely. By this time it was apparent our aircraft couldn’t leave the flight deck, so I shut down the engines to decrease the velocity and severity of our imminent impact.

During this chaotic ride, as my aircraft drifted out of the landing area, we entered the area of the flight deck occupied by previously landed aircraft and the personnel attending to them. The reactions of individuals confronted with my uncontrolled aircraft ran the gamut, from frozen disbelief as I ran them over to instinctive leaping to the side, apparently warned only by the sound of my screeching landing gear, or perhaps the abnormal vibration of its contact with the flight deck.

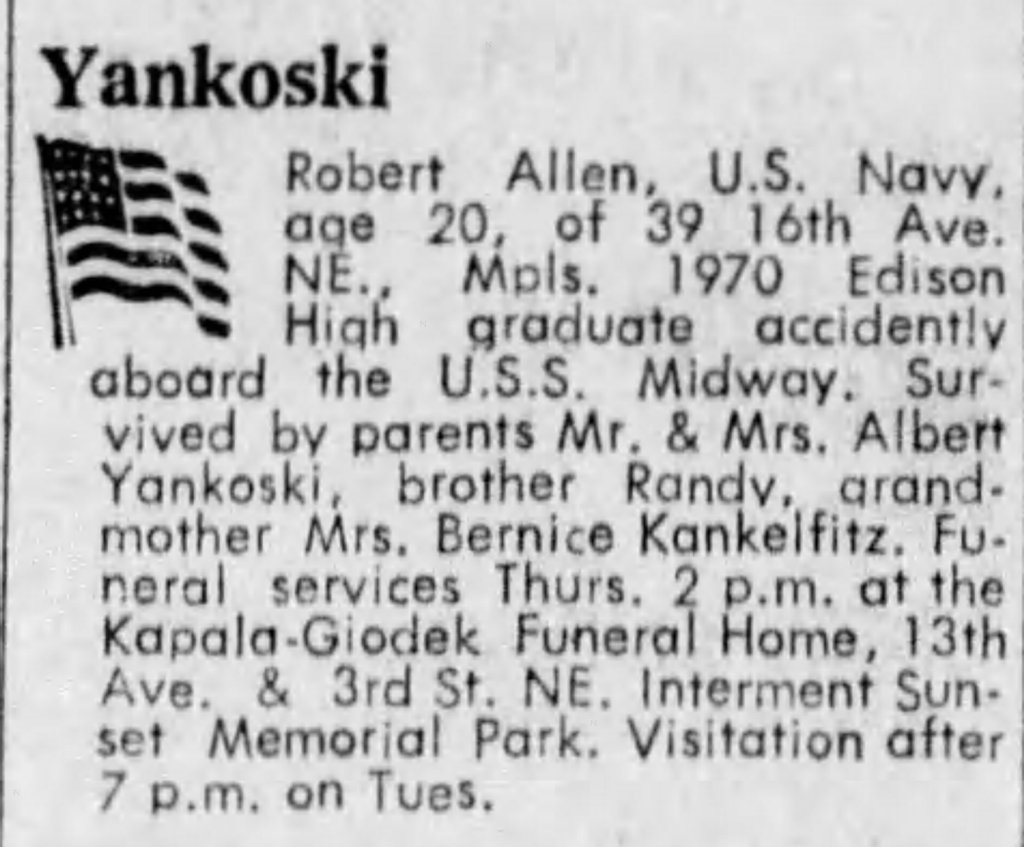

The crash injured the pilot, and over 20 people on the deck. Robert was 1 of 4 sailors killed in the accident. The Bombardier/Navigator was killed as well.

Robert’s remains were returned to Minnesota for burial.

Robert is buried at Sunset Memorial Park in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

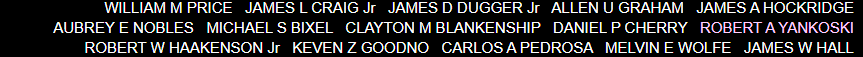

Robert’s name is inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. on Panel 1W, Line 83.

Inscribed on the same line as Robert are the names of the 4 shipmates that died in the same incident. Aubrey Nobles, Michael Bixel, Clayton Blankenship, and Daniel Cherry,