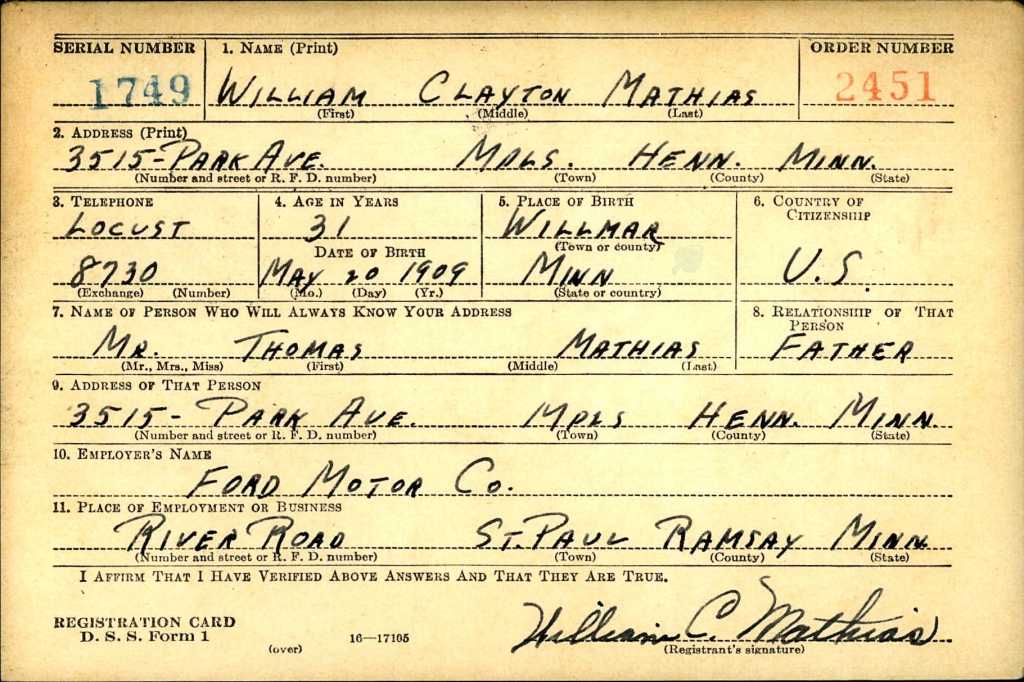

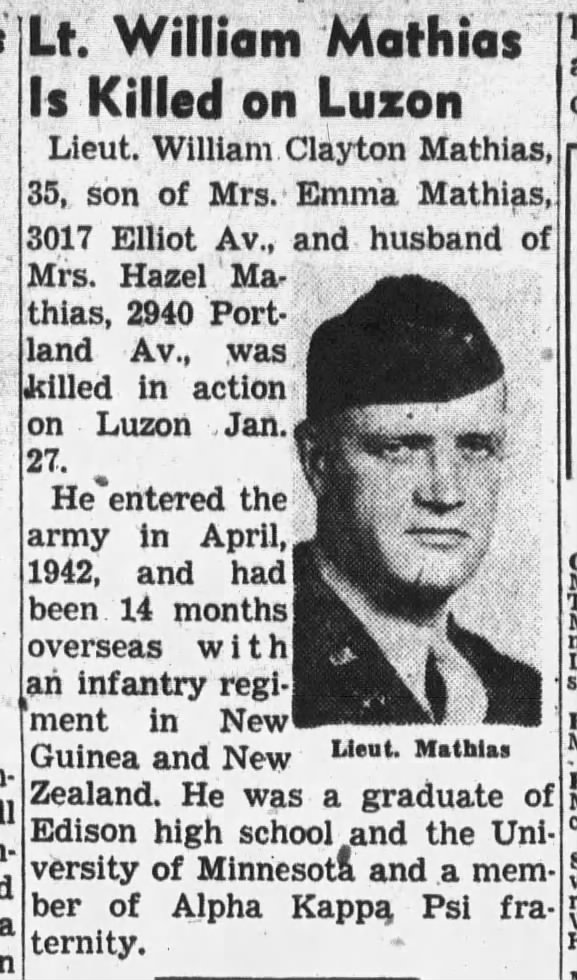

20May1909 – 27Jan1945

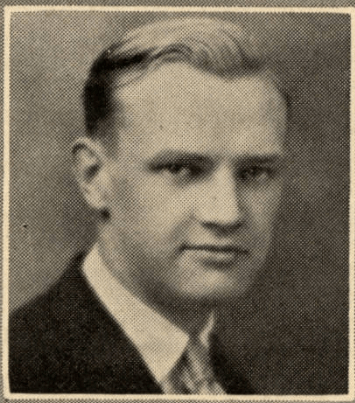

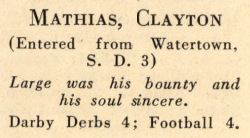

Edison Days

William (Clayton) graduated with the Class of 1927. He played football and was a member of the Darby Derbys service club.

After graduation he attended and graduated from the University of Minnesota.

Military Service

Rank: 2nd Lieutenant

Branch: United States Army

Unit: Headquarters Company – 172nd Infantry Regiment – 43rd Infantry Division

William entered service on 21Apr1942. It is unknown where he attended basic training. In May 1943 he was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant at Fort Benning, Georgia.

William likely joined the 172nd Infantry Regiment in New Zealand as a replacement soldier after the unit had been in heavy combat in New Georgia in the Pacific theater.

In July 1944 the unit was sent to Aitape on the Northern coast of New Guinea to relieve elements of other U.S. units and securing the area against potential Japanese counterattacks.

The regiment engaged in extensive patrols and reconnaissance operations, particularly around Tadji airfield and along the Driniumor River.

Japanese forces launched a major counteroffensive in mid-July, aiming to retake Aitape. This led to the intense Battle of the Driniumor River. The 172nd, alongside the 169th and 103rd Infantry Regiments, helped hold and reinforce the defensive line. The battle involved bitter close quarters combat in dense jungle terrain. By late July, patrols turned into defensive actions against Japanese infiltrations. On 8Aug1944, the division shifted to the offensive, pushing back remaining Japanese forces and ending organized resistance by the end of the month.

The following excerpt is from a history of the 43rd Infantry Division.

The ships were loaded and ready. On the rainy morning of December 26th, 1944, the men of the 43d Infantry Division marched to the beach at Aitape laden with bazookas, machine guns, mortars, grenades, and packs. Loading was accomplished speedily. Two days later, after all ships and personnel had participated in a complete landing, the ships sailed. The Sixth Army convoy speeding northward seemed to s-stretch from horizon to horizon. The 43d Infantry Division and its attached troops were combat loaded on eight APAs, three APs, four AKAs, sixteen LSTs, ten LSMs and two LSDs. The men were as calm as was the ocean on the voyage and even the propaganda broadcasts of Japan’s famed Tokyo Rose couldn’t excite them, though she said, “I am broadcasting to you Munda Butchers. The Japanese Army knows that you are headed for Luzon and that you are going to land at Lingayen Gulf.” Then she would tell what to expect there, and it sounded as if the American invaders could expect the might of the entire Japanese Army. The men only shrugged their shoulders and continued reading their books and playing cards.

Then came the morning of January 9, 1945. The roar of the Naval guns sounded the unending roll of a thousand bass drums as they bombarded the shoreline. This was a sight no one who saw it will ever forget. And then it came. The loudspeakers aboard the ships blasted out with “Boat team 48 to Red 5.” “Boat team 48 to Red 5.” Then “Boat team 51 to Green 8,” and this continued until the assault troops had all climbed down the rope nets into the small landing craft lying by the sides of the ships. Soon Lingayen Gulf was full of amphibious tanks and tractors, landing craft, and numerous other types of boats circling in small groups as they prepared for the assault to the beach. On signal they all turned and headed towards the shore forming V-shaped waves. The amphibious tanks and tractors landed first depositing thousands of troops which rapidly drove their way inland. No enemy small arms fire was encountered at the beach line, but casualties mounted from heavy mortar and artillery fire, from concealed guns in the high hills to the northeast.

Reorganization was hastily effected by the 103d Infantry on the right pushing into San Fabian, the 169th Infantry in the center moving forward toward Mabilao and the 172nd Infantry on the left straining to gain the high ground north of Alacan. As the infantry pushed forward, they began to uncover the Japanese outposts, but by nightfall a substantial area in the beachhead had been gained. On the second day, the leading elements on the division’s north flank encountered fierce and determined resistance in the rugged hills ·north and east of Alacan, and on the south, other elements of the division were battling their way toward San Jacinto against scattered enemy resistance.

Meanwhile, on the beach, it was determined that Beach White 2, the middle

beach was the only one in the entire Army beachhead suitable for landing the numerous LSTs on which the great bulk of mobile equipment of the assault force was loaded. This made the immediate destruction of enemy artillery on the hills overlooking this beach imperative and the order was sent down that these strong points must be overrun at all cost. But the enemy had been preparing these positions for two years, and only through the most bold and daring maneuver was this mission accomplished. The men who were there will never forget how the 172nd Infantry knifed its way over the sugar-loaf hills to seize the J ap supply base at Rosario; or the 169th daring night march to out-flank the enemy bastions on Hill 355; or the skillful encirclement of Hill 200 by the 103d Infantry.

By the last of January assigned missions were completed. The division had overrun 125 heavy artillery positions, engaged enemy tanks for the first time on Luzon, and destroyed the Jap in his supreme effort, in the pillboxes guarding the road to Baguio. The division with its attached units found itself deployed on a front of twenty-five miles, depleted in strength, hilt continuing the attack. Regarding this initial action, the First Corps Commander, Major General Innis P. Swift, told the division after the campaign, “I am proud of you and I am proud of your commander. When this Division landed at Lingayen Gulf it had to fight the whole accursed Jap force, and don’t let anyone tell you differently.

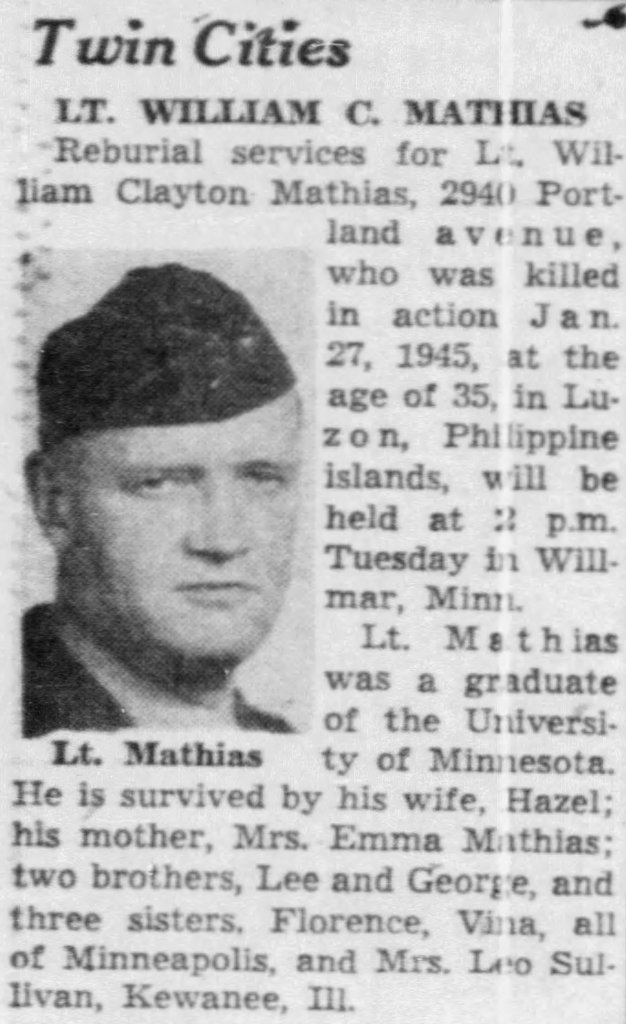

William was killed in action on 27Jan1945. The circumstances if his death are unknow.

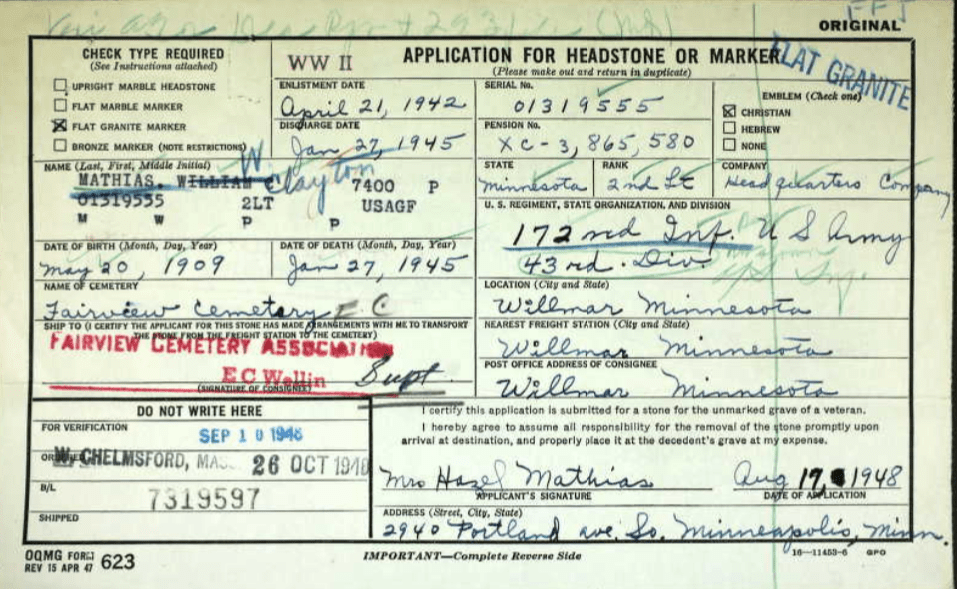

William was originally buried in a temporary military cemetery in the Philippines. In 1948 his remains were returned to the United States for reburial.

William is buried at Fairview Cemetery in Willmar, Minnesota.